New ‘He Gets Us’ Super Bowl Ad Targets American Materialism, Points Viewers To Jesus

The He Gets Us campaign has returned to the Super Bowl with a direct prod at our national appetite for more. In a commercial season built on flash and desire, this spot asks a sharper question: can buying and consuming ever truly satisfy? The ad throws a cultural mirror at viewers and dares them to look honestly at what they chase.

This is the fourth straight Super Bowl appearance for the project, but it’s the first time the message openly calls out materialism as a competing gospel. That contrast matters because the Super Bowl night often celebrates excess and spectacle. Dropping a reflective, spiritually framed spot into that mix is meant to be jarring on purpose.

The 60-second piece unfolds as a series of quick, familiar images meant to land like small punches to the conscience. It opens with a line that’s both blunt and memorable: “The one who dies with the most toys wins.” Snapshots of selfies, Las Vegas-style revelry, flexing bodies, and late-night scrolling cram the screen, all underscored by a voice insisting we need to be more, newer, and constantly entertained.

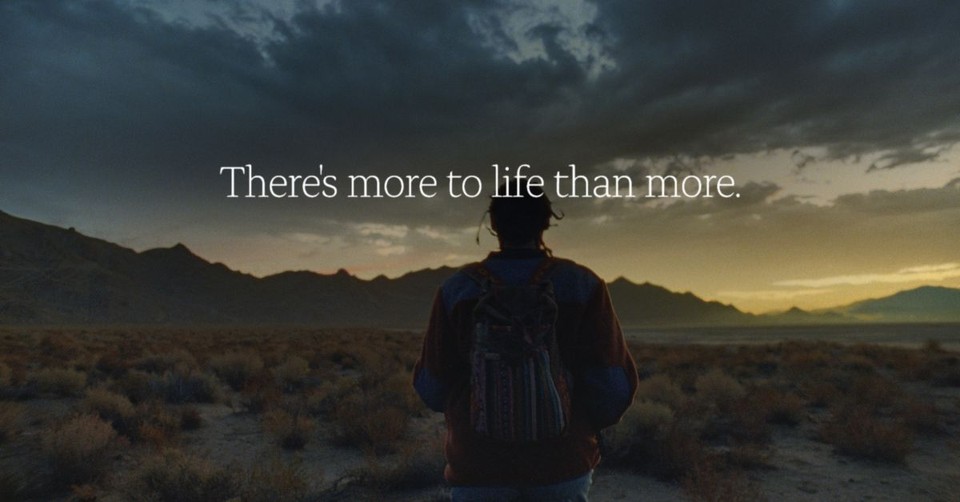

Then the tempo slows and the edit gives us a breath — a young woman alone in an open field under a vast sky. The cinematic shift pushes viewers from appetite toward reflection and invites a quiet question about what actually endures. It’s a short, cinematic sermon: stop chasing quantity and consider depth.

Ad Message And Reception

Tyler Johnson, who oversees impact for the group behind the ads, frames the spot as rooted in Scripture and the life of Jesus rather than a marketing tactic. He says the campaign exists to correct cultural currents that place endless acquisition at the center of human identity. That framing intentionally pushes a spiritual alternative to consumerism.

Johnson has addressed critics who say the spots don’t deliver the full gospel in a single ad. “It’s not that we would be against that, but the approach we’re taking is just a different approach,” he said, noting the commercial’s role is to open doors, not to preach a complete theological roadmap on television. The strategy is to inspire curiosity and point people to places where fuller conversations can happen.

The creators are clear about the practical aim: make something that delights, then reveal a spiritual hinge at the end so viewers rewind their thinking. They want to “incite curiosity, to make people take one step closer” to asking who Jesus was and whether his message matters today. That small step, they argue, can lead to deeper exploration on a website and in local churches.

Another common critique is the price tag — Super Bowl spots cost millions — and some see that as an odd way to spend ministry dollars. Johnson responds with a question of his own: “What is it worth to raise the public conversation about Jesus?” For him, the investment is judged by whether it creates fresh, public curiosity about the Christian story.

The campaign has reached massive audiences in recent years and driven millions to learn more, showing how a single cultural moment can multiply into sustained interest. For those who pause at the final image and want answers, the campaign’s online hub offers videos, articles, and pathways to local congregations. The goal is not to win an argument on TV but to open up honest conversations that point to the person at the center of the Christian claim.

Whatever people make of the creative choices, the spot aims to reinsert a spiritual question into a mainstream moment and to remind viewers that lasting joy is not bought at checkout. If the ad nudges even a handful of viewers away from the treadmill of more and toward a search for what lasts, its makers will count that as success. The work now is to keep those conversations going after the game ends.